Introduction

Attacking a favorite IPO transaction structure used by the private equity industry—the Umbrella Partnership Corporation, or “Up-C” —has become an emerging trend in the plaintiffs’ bar and one that all sponsors should have on their radar. Numerous sponsors and their funds have used the Up-C structure in IPO transactions in recent years, both for their portfolio companies and for themselves—and for good reason. The Up-C allows investors in an LLC that is treated as a partnership for tax purposes to access the public securities markets by taking the company public while preserving many of the tax efficiencies of a traditional partnership ownership model. Moreover, when those investors eventually liquidate their partnership units, they sell them to the public company in exchange for (i) public shares on a 1:1 basis (which are then sold for cash) plus (ii) additional cash consideration equal to a portion (usually 85%) of the cash tax savings realized by the public company attributable to those units in future years through a contract called a Tax Receivable Agreement (TRA).

Although many investors appreciate the opportunity to invest in these newly public companies, as with any evolving deal structure, increased use brings increased scrutiny. So it is that, as Up-C investments have matured, the structure increasingly has been challenged by minority investors contending that the Up-C model permits pre-IPO investors to “double dip” on cash distributions made by the business and unfairly capture tax benefits that should inure ratably to the public shareholders. Some of these minority investors have turned to litigation as a means of addressing perceived inequities in the Up-C model. Ironically, in a shift from typical stockholder suits, in the Up-C context, companies that are performing well at or post-IPO are targeted for litigation. Instead of suing to recover for losses, investors—or, rather, their lawyers—bring suit alleging the appearance of conflicts and unfair allocation of the upside resulting from the cash tax savings the structure affords.

This inversion in risk profile, and the attack on a common and advantageous tax structure, make the Up-C litigation trend one worth watching closely. To aid investors, we offer the following primer, in which we first describe the common features of an Up-C IPO transaction and the Up-C ownership model, and then analyze recent lawsuits involving Up-Cs. We focus in particular on portfolio company litigation, and the particular challenges to post-IPO cash distributions made by Up-Cs and the impact and unwinding of TRAs entered into in connection with Up-C IPO transactions.

Structure and Benefits of Up-C IPOs

As many in the industry have long recognized, Up-Cs can offer important advantages when taking an investment public. Private equity funds often hold their investments in portfolio companies via structures that are treated as pass-through entities for U.S. tax purposes, like limited partnerships or limited liability companies. In a traditional portfolio company IPO, pre-IPO investors experience no shift in the company’s tax status in connection with the IPO— it is a corporation before and after. However, for a portfolio company treated as a partnership for tax purposes, the sponsor has a choice of whether to incorporate the company to take it public or instead to go public via an Up-C structure. If the company is incorporated, it becomes a traditional corporation subject to corporate entity level taxation, and pre-IPO investors lose the benefit of the pass-through status. In addition, it is generally not possible for pre-IPO investors to deliver a stepped-up tax basis to the company on a sale of interests, meaning there is no possibility for realizing the enhanced value that may come from a TRA. A key appeal of the Up-C structure is its ability to preserve some of the benefits of partnership status for pre-IPO investors, and the value enhancement of a TRA, while inviting public investment.

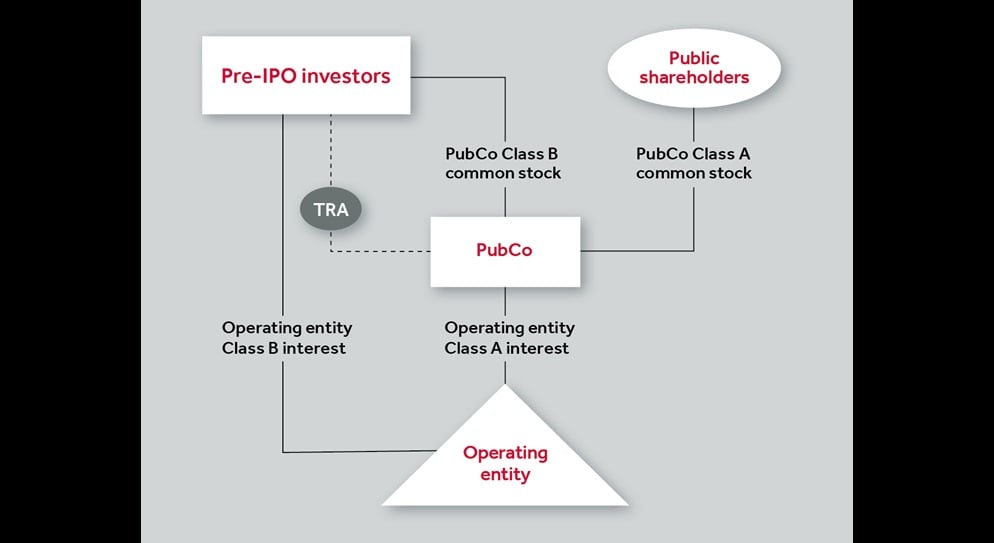

In an Up-C IPO, the sponsor creates a holding company (“PubCo”), which is named the managing member of—and thus controls—the operating pass-through entity and is capitalized by units of the operating entity representing typically between 30–40% of the economic interest in such entity (which PubCo acquires with the proceeds of the IPO). Pre-IPO investors retain units in the operating entity representing the remaining 60–70% economic interest in such entity. The operating entity continues operating the underlying business and holding its principal assets.

In the IPO, PubCo issues two types of shares: (1) Class A common stock, which is issued to public investors and carries the economic entitlements of ownership in PubCo but only a small percentage of voting rights; and (2) Class B common stock, which is issued to pre-IPO investors and carries a majority of the voting rights in PubCo, but no economic rights (as these investors continue to hold their economic interests via units in the operating pass-through entity).

PubCo and the pre-IPO investors also typically enter into two agreements in connection with the IPO. First, they enter into an exchange agreement allowing pre-IPO investors to exchange their units in the operating company for cash or shares of Class A common stock, typically on a 1:1 basis. Second, pre-IPO investors and PubCo enter into a TRA entitling pre-IPO investors to a percentage of any tax benefit derived by PubCo from the Up-C structure following a sale of the pre-IPO investor’s units to PubCo (typically 85% of the realized cash tax benefits derived by PubCo in the future, usually paid out for all practical purposes over the following 16 years). Such benefits are generated by a stepped-up tax basis in its assets PubCo acquires from the pre-IPO investors – it is a separate tax asset that is created in the exchange, with benefits split between PubCo and the pre-IPO investors. The TRA also typically provides for a lump sum payment to pre-IPO shareholders in the event of a change in control transaction, calculated based on certain valuation assumptions.

The following figure illustrates the resulting structure after consummation of the Up-C IPO:

In addition to payments under the TRA, pre-IPO shareholders also benefit from continuing to hold their economic interest at the operating entity level, which remains a pass-through entity for those investors not subject to corporate tax (although their exchange price is tied to the public share price, which presumptively is burdened by the corporate tax paid by PubCo).

Litigation Challenges to Up-C Structures

For all the benefits the Up-C IPO offers to investors, the structure has not been without its critics. As illustrated above, after completion of the Up-C IPO, pre-IPO investors remain in effective control of the underlying business through their voting control over PubCo (provided that such investors have not elected to exit the investment altogether). The separation of these investors’ voting interest at the PubCo level from their economic interest at the operating entity level, however, increases risk that decisions made at one level or the other could be subject to challenges that pre-IPO investors’ are attempting to disproportionately benefit themselves over public shareholders. Such structural risks attendant to the Up-C form mean that, unless the board implements procedural protections for minority shareholders, pre-IPO investors’ governance decisions are likely to be reviewed under the strict “entire fairness” standard of review.

Garfield v. Blackrock Mortgage Ventures, LLC, et al. (Del. Ch.), Case No. 2018-0917, a case involving an effort by BlackRock and Highfields Capital to exit an investment that they had taken public via an Up-C IPO, exemplifies these risks. There, the plaintiff, a minority shareholder in the PubCo, sued to challenge the exit transaction and the Chancery Court held that it was subject to entire fairness review because the pre-IPO investors constituted a control group and were differently situated from minority shareholders with respect to the exit.

More recently, litigation involving Up-C structures has arisen in two other areas of interest for private equity sponsors: (1) the operating entity’s payment of dividends or other cash distributions in the post-IPO period and (2) early termination of TRAs, as PubCos undergo further change-in-control transactions or pre-IPO investors seek to terminate their TRAs early as part of larger restructuring transactions.

Distributions

One area in which the complexity of the Up-C structure has spawned litigation is the payment of dividends or other distributions by the operating entity. Because pre-IPO investors control the decision regarding whether and when the operating entity will distribute excess cash to unitholders, some minority PubCo shareholders have attempted to challenge these distributions as self-interested transactions.

In particular, operating company dividends have been challenged as inequitable “double dipping” transactions that unfairly benefit pre-IPO shareholders. The “double dip” theory is usually presented as follows: When the operating company pays a dividend, cash is distributed (1) directly to pre-IPO shareholders on account of the units representing their economic interests in the operating company and (2) to PubCo on account of its units representing the remaining economic interest in the operating company. Dividends received by PubCo are then typically held as cash on its balance sheet to the extent that they are not needed to pay corporate taxes. Although such distributions are pro rata among the unitholders of the operating partnership, because pre-IPO investors have the right to exchange their units in the operating company for Class A shares in PubCo, they arguably benefit twice from the dividend—once at the operating company level in the form of cash from the dividend and again at the PubCo level in the form of cash on PubCo’s balance sheet from the dividend. Claims that these dividends constitute breaches of the fiduciary duty of loyalty are bolstered by the fact that pre-IPO investors remain in effective control of all of the relevant corporate decisions through their voting control over PubCo.

At least one lawsuit has been filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery espousing this “double dipping” theory of liability in connection with operating company dividends: Schumacher v. Mariotti, Case No. 2022-0051 (Del. Ch.). Defendants have moved to dismiss on several grounds, including that shareholders were fully informed of the Up-C structure and its potential consequences before purchasing their shares. The Chancery Court will hear argument on the motion in July 2023.

Early TRA Termination

Another feature of Up-C transactions that presents litigation risks is early termination of TRAs. Such contracts typically pay out most of their value in the first 16 years following an exit by a pre-IPO investor, including a sponsor. The 16-year period in most cases will extend well past the termination date of most closed-end funds. As a result, sponsors understandably look for options to monetize their TRA rights before the end of the contract’s lengthy term. While a relatively nascent market exists to purchase TRAs, the buyer of the TRA has in certain cases been the related PubCo itself.

As noted above, TRAs are subject to multiple contingencies. For example, the PubCo may incur tax liability such that it benefits from a step up in tax basis made possible by the Up-C structure—and thus trigger an obligation to make payments to pre-IPO investors under the terms of the TRA. Or, certain change-in-control transactions may be beneficial in light of the fact that they also may trigger payments to pre-IPO investors under TRAs. Both of these contingencies recently have spawned shareholder litigations arising from typical Up-C structures.

For example, IBEW Local Union 481 v. Winborne, Case No. 2022-0497 (Del. Ch.), concerns an effort by KKR and Silver Lake to monetize rights under TRAs after they had otherwise exited their investment in GoDaddy Inc. There, plaintiffs filed a shareholder derivative action seeking to challenge GoDaddy’s $850 million buyout of the TRAs entered into in connection with GoDaddy’s April 2015 Up-C IPO. Plaintiffs alleged that the price of the buyout was excessive and constituted a breach of the duty of loyalty in light of the fact that directors affiliated with KKR and Silver Lake remained on the board. The decision whether to agree to the buyout was not submitted to shareholders for approval, and GoDaddy had never earned taxable income (rendering it possible that it would not trigger payments to the sponsors under the TRA for an extended period). Defendants have moved to dismiss on several grounds, including that the board’s formation of a special committee to negotiate the buyout entitles it to the deference of the business judgment rule. The Chancery Court will hear argument on the motion to dismiss at the end of May 2023.

Similarly, in Pullan v. Skonnard, Case No. 2021-0043 (Del. Ch.), plaintiffs filed a shareholder derivative action seeking to enjoin a take-private transaction, a component of which included a $127 million payment to Pluralsight’s private equity sponsors under an amendment to the terms of a TRA entered into in connection with Pluralsight’s May 2018 Up-C IPO. Plaintiffs alleged that the take-private transaction should be enjoined because the board was conflicted with respect to the negotiation of amendments to the TRA and that the disclosures in connection with proxy solicitation for the transaction were insufficient. Plaintiffs dropped their motion to preliminarily enjoin the transaction after defendants agreed to limited document discovery and voluntarily dismissed the case in January 2023 after receiving additional disclosures in connection with the same.

Looking Ahead

Every structure comes with risk, and the Up-C structure is no exception. The Up-C structure allows investors to address complex problems involving the intersection of tax, capital markets and M&A, and its advantages continue to outweigh its drawbacks for most deals. But, as with many creative solutions to complex problems, additional risks are emerging over time. We are closely monitoring this evolving landscape, as litigious shareholders and their counsel are beginning to target features typical of Up-C structures and the Delaware Chancery Court is poised to provide additional guidance in these areas in the Schumacher and Winborne cases scheduled to be heard this summer. Sponsors should be alert to these developing issues as they begin strategizing their exits from investments in Up-C structures and wind-downs of TRAs entered into in connection with such transactions. Strong arguments exist to defend Up-C structures and TRA payouts, but each case is different, and sponsors are well-advised to be prepared for possible future challenges.

Private Equity Report Spring 2023, Vol 23, No 1