Key Takeaways:

- This Debevoise In Depth summarizes key copyright developments from the past year and provides insights on what to expect heading into 2025.

- 2024 saw a flurry of copyright activity in wide-ranging contexts. In one of the most high-profile cases of the year, the Supreme Court weighed in on the statute of limitations for copyright damages in Warner v. Nealy, finding that there is no distinct three-year limit on copyright damages in jurisdictions that follow the discovery rule. The Supreme Court will have another opportunity to address this issue in RADesign, Inc. v. Michael Grecco Productions, Inc. in which plaintiff has petitioned for certiorari and specifically asked the Court to address the viability of the discovery rule.

- District and circuit courts continued to grapple with what the Supreme Court’s 2023 Warhol decision meant for fair use in cases dealing with documentary film-making, e-books, tattoos, photos, and memes. Key issues were the degree of transformativeness necessary for fair use, as well as the relationship between transformativeness and commercialism. These fair use issues are far from resolved and we’ll continue to see the courts address these issues in 2025.

- In the musical context, we saw plaintiffs continuing to allege infringement of hit songs such as Ed Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud” and Miley Cyrus’ “Flowers.”

- This year we expect to see more AI suits filed, both by individual creators and corporate rightsholders, and anticipate that courts will begin to issue decisions on the merits of thorny AI issues such as training data and fair use.

As we stride full force into 2025, we are taking a moment to reflect on the copyright rollercoaster that was 2024. It was a year of high-stakes showdowns and headline-grabbing drama in the legal world, from a Supreme Court ruling that reshaped the landscape of copyright damages to the lingering aftershocks of the 2023 Warhol decision. All in all, 2024’s copyright cases kept artists, techies, and legal eagles on the edges of their seats.

2024 also saw the music industry hit some high notes in a wave of ongoing lawsuits, while generative AI took center stage in a digital-age clash between creativity and technology that will have a lasting impact on how we think about art, innovation, and ownership in the new year and beyond.

If 2024 was a show, 2025 promises to be the encore no one can afford to miss. Expect AI to continue stealing the spotlight, music industry lawsuits to keep the hits rolling, and big questions about heavy hitters like fair use to have their time in the limelight.

The Supreme Court Weighs in on Copyright Damages

Hot on the heels of 2023’s blockbuster Warhol decision, the Supreme Court once again weighed in on copyright in 2024. This time, the justices tackled the statute of limitations for damages in Warner v. Nealy.

As background, the Copyright Act bars claims that are not “commenced within three years after the claim accrued,” but does not define what it means for a claim to have “accrued.” 17 U.S.C. 507(b). In interpreting this provision, the majority of courts follow the so-called “discovery rule,” which allows plaintiffs to recover damages for acts that occur outside of the three-year statute of limitations as long as the suit was filed within three years of discovery of the infringement. This stands in contrast to the so-called “injury rule,” which dictates that the three-year statute of limitations begins when the alleged infringement occurs, giving a plaintiff three years after that to recover damages, regardless of when the plaintiff learns of the infringement.

Among those courts that follow the discovery rule, courts were further split on how the issue of damages should be handled. Some courts, most notably the Second Circuit, allowed plaintiffs to sue for past undiscovered infringement, but not to recover damages for anything that occurred more than three years from the filing of the lawsuit. See Sohm v. Scholastic, Inc., 959 F.3d 39, 49-50 (2d Cir. 2020). The Ninth Circuit, by contrast, held that plaintiffs could recover damages for infringement outside the three-year period.

Warner Chappell Music Inc. et al. v. Sherman Nealy et al.

In May of this year, the Supreme Court finally addressed the scope of recoverable damages under the Copyright Act in Warner Chappell Music, Inc. v. Nealy, 601 U.S. 366 (2024).

The case had its impetus in a music publishing company formed by Shearman Nealy and Tony Butler in the early 1980s. After the company released a handful of songs, Nealy was sent to prison for 15 years on drug-related offenses. While Nealy was incarcerated, Butler licensed several of the songs to Warner Chappell without Nealy’s permission; the songs were then repurposed by artists such as Flo Rida and The Black-Eyed Peas. The infringement continued for years, but Nealy did not learn of it until he was released from prison in 2015. He sued in 2018.

The Eleventh Circuit follows the discovery rule, so Nealy’s claims were not time-barred, but it was unclear whether damages for conduct occurring more than three years before Nealy filed suit were recoverable. The district court said no, the Eleventh Circuit said yes, and the Supreme Court agreed with the latter. The Court reasoned that the Copyright Act did not allude to any separate statute of limitations for recovering damages, and that imposing a three-year limit on damages would “gut” the entire notion of the discovery rule. Id. at 372-73. Though Nealy resolved the question of whether damages were time-barred in a discovery-rule jurisdiction, the Court did not address the initial question of whether copyright claims should follow the discovery rule or the injury rule in the first instance.

The big question going forward: will the Court take another swing at the issue and settle once and for all whether the discovery rule should apply to copyright claims? Justice Gorsuch’s dissent provides a clue, arguing that the discovery rule may be inappropriate in the copyright context. On the other hand, the Supreme Court previously denied certiorari for Hearst Newspapers, LLC v. Martinelli in May 2024, which dealt with this very issue. The Supreme Court will have another opportunity to address this issue in RADesign, Inc. v. Michael Grecco Productions, Inc., a case in which the copyright holder Michael Grecco Productions did not learn of shoe designer RADesign’s infringement of copyrighted photographs until more than four years following the date on which infringement began. RADesign has petitioned for certiorari, asking the Court to address the viability of the discovery rule. While there is no guarantee the Supreme Court will grant RADesign’s petition, plaintiffs and potential defendants would do well to monitor this case and keep an eye on the clock when evaluating the strength of potential copyright claims going forward.

Fair Use: Warhol in Action

The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Warhol sent shockwaves through ongoing copyright litigation and already has had a major impact on fair use jurisprudence, sparking a thorny debate on transformativeness and commercialism that we expect will continue into 2025.

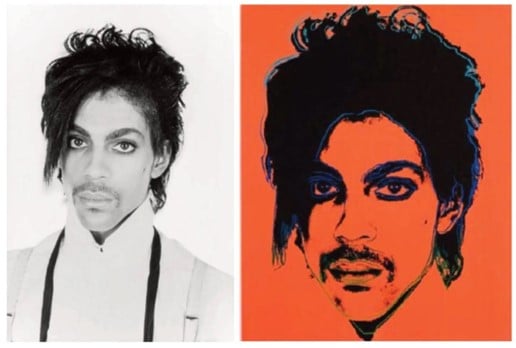

The Warhol case had its genesis in a photograph of the musician Prince that Goldsmith, a professional photographer, licensed to Vanity Fair in 1981. Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. 508, 514-15 (2023). The artist Andy Warhol then created an illustration based on the photograph titled “Orange Prince,” which “crop[ped], flatten[ed], trace[d], and color[ed] the [original] photo but otherwise [did] not alter it.” Id. at 522. In 2016, Goldsmith sued the Andy Warhol Foundation for infringement of her photograph based on the Foundation’s licensing of “Orange Prince” to Condé Nast. In assessing Goldsmith’s claim, the Supreme Court examined only the first fair use factor, the “purpose and character of the use,” concluding that this factor favored Goldsmith. Id. at 550.

Left, Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince; right, Warhol’s 1984 Orange Prince.

In assessing transformativeness, the Supreme Court’s opinion focused on the similarity of how the works were used (i.e., as images accompanying magazine articles), rather than the similarities of the works’ aesthetic characteristics. It was not enough, explained the Court, that “Orange Prince” had different visual characteristics from Goldsmith’s photograph, because there was no transformation in purpose between the two works. The Court noted that the purposes of the two works were very similar: “Orange Prince” was licensed “to illustrate a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince,” a purpose “substantially the same” as the original photo’s purpose. Id. at 545. The Court also highlighted the commercialism of “Orange Prince” as weighing against fair use, explaining that transformativeness “must be balanced against the commercial nature of the use. If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use.” Id. at 532-33.

This year, we saw courts grapple with Warhol’s implications for fair use in contexts as diverse as tattoos, e-books, memes, and documentary films; we expect the number of industries impacted by the Warhol decision will only increase in the year ahead.

Whyte Monkee Prods., LLC v. Netflix

This year’s fair use debates were filled with colorful characters, and Joe Exotic of the Netflix smash hit documentary series “Tiger King” was no exception. In Whyte Monkee Productions, LLC v. Netflix, Inc., 97 F.4th 699 (10th Cir. 2024), the plaintiff was a production company that sued Netflix for using its video clip in the popular “Tiger King” series. The clip in question was a 66-second excerpt of a 23 minute and 52 second video, captured at the funeral of Joe Exotic’s husband. The clip was used in the Netflix series to illustrate Mr. Exotic’s megalomania and showmanship.

The district court originally granted summary judgment for Netflix, finding that the inclusion of the clip constituted fair use. However, the Tenth Circuit reversed the decision and remanded for further fact finding into the market harm caused by Netflix’s use of the clip. Notably, the court held that under Warhol, Netflix’s use was not sufficiently transformative to qualify as fair use because the documentary did not comment on or criticize the clip itself, “but rather targeted a character in the composition.” Id. at 714.

Numerous industry and legal scholars interpreted the Tenth Circuit’s ruling to require criticism or commentary on the work itself for a use to satisfy the first fair use factor, sparking substantial backlash in the form of a flurry of amicus briefs. In response, the Tenth Circuit vacated its prior opinion and granted Netflix’s petition for a rehearing en banc in May 2024. Whyte Monkee Prods., LLC v. Netflix, Inc., 101 F.4th 787 (10th Cir. 2024). The court ordered supplemental briefing and further oral argument on the impact of the decision on documentary filmmaking, addressing topics including (1) the relevance of fair use jurisprudence to the use of film clips for “preamble” purposes in documentaries; (2) the impact of Warhol on said fair use jurisprudence; and (3) whether the court’s prior analysis had properly accounted for Warhol and related caselaw. Id.

Hachette v. Internet Archive

In Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive, 115 F.4th 163 (2d Cir. 2024), Warhol was applied in an epic battle of the books as publishers squared off against the self-proclaimed library of the internet. The Second Circuit held that under Warhol, a nonprofit digital library’s publication of free digital versions of print books on its website was not fair use. Plaintiffs were four publishing companies that argued that the Internet Archive’s activities infringed their copyrights in a variety of books. The Internet Archive argued that its digital library, which operated according to the principle of “controlled digital lending” (a library practice that allows patrons to concurrently borrow the number of digital copies of a book of which the library owns physical copies) was fair use.

The district court granted the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment on the issue of fair use in 2023, holding that all four factors of the fair use test favored the plaintiffs. Defendants appealed to the Second Circuit, which unanimously affirmed the district court’s ruling that the Internet Archive’s library did not constitute fair use.

In finding that the defendant’s use was not transformative, the court quoted Warhol, stating that “while the right of copyright owners to prepare derivative works is ‘subject to’ fair use, an ‘overbroad concept of transformative use . . .that includes any further purpose, or any different character, would [improperly] narrow the copyright owner's exclusive right to create derivative works.’” Id. at 180 (quoting Warhol, 598 U.S. at 529). Instead, the court explained, the Internet Archive’s digital books “serve the same exact purpose as the originals: making authors’ works available to read. [The Internet Archive]’s Free Digital Library is meant to—and does—substitute for the original Works.” Id. at 181. Though the books were converted from physical copies to digital ones by the Internet Archive, the court noted that per Warhol, “changing the medium of a work is a derivative use rather than a transformative one.” Id. (citing Warhol, 598 U.S. at 529).

A particularly notable aspect of the Hachette ruling is that the non-commercial nature of the Internet Archive’s use was not enough to tip the first fair use factor in the Internet Archive’s favor. In Warhol, the Supreme Court held that commercialism was “relevant” but “not dispositive,” and directed courts to “weigh [commercialism] against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or different character.” Warhol, 598 U.S. at 531. However, Warhol provided little guidance on how to execute that instruction—particularly given that the Court also held that transformativeness remains the “central” focus of the first fair use factor. See id. at 542. Struggling with how to weigh commercialism, the Second Circuit did very little with its finding that the Internet Archive’s use was non-commercial, and merely held that “because [the Internet Archive’s] use of the [w]orks is not transformative, the first fair use factor favors [the publishers].” 115 F.4th at 186.

Hachette was hailed by publishers and other rightsowners as a vindication of their rights in the face of widespread online piracy. Ultimately, this case signals that moving forward, even non-profit uses of a work may not qualify for fair use if the use is not sufficiently transformative.

Tattoo Cases

Several district courts also have applied Warhol’s fair use principles in the context of tattoos, evoking complicated copyright concerns due to industry norms surrounding copying. One such case was Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, No. 21 CV 1102, 2024 WL 4327404 (C.D. Cal. May 3, 2024).

Jeffery Sedlik, a photographer, sued celebrity tattoo artist Kat von D for copyright infringement after she tattooed a client with a copy of a photograph he had taken of jazz icon Miles Davis. Sedlik alleged that both von D’s social media posts depicting the photograph and the tattoo itself constituted copyright infringement.

Left, Sedlik’s photo; right, von D’s tattoo.

A jury returned a verdict in von D’s favor in January 2024, concluding, among other things, that the tattoo and social media post constituted fair use. Sedlik then moved for renewed judgment as a matter of law on issues including fair use. In May 2024, the court denied Sedlik’s motion.

In contesting the jury verdict as to fair use, Sedlik argued that under Warhol, the jury’s finding of fair use with respect to the social media posts was contrary to the clear weight of the evidence because the uses “were not transformative, were commercial, and harmed the market for Sedlik's photograph.” Id. at *4. The court disagreed, explaining that while Warhol stood for the proposition that “a work that targets another. . . is transformative because it needs to conjure up the other to make its point or fulfill its purpose,” a work could also be transformative if a plaintiff could show “another ‘compelling justification for the use,’” even if there was no need for the work to target the original work. Id. at *4 (quoting Warhol at 540). Here, the court found that the social media posts served to document von D’s “life and creative process.” Id. The court similarly discounted Sedlik’s arguments as to commerciality and market harm, stating that neither factor was dispositive.

Sedlik has since appealed the ruling to the Ninth Circuit.

Philpot v. Independent Journal Review

The intersection between celebrity likenesses and fair use in the wake of Warhol was also explored in a February decision from the Fourth Circuit in Philpot v. Independent Journal Review, 92 F.4th 252 (4th Cir. 2024).

Photographer Larry Philpot filed copyright infringement claims against a news website known as Independent Journal Review (“IJR”) when it used Philpot’s photographs of musicians Willie Nelson and Kid Rock to accompany articles without Philpot’s permission. Philpot, who often made his works available under a Creative Commons license, argued that IJR had failed to adhere to the terms of the license, which required attribution and adherence to specific usage guidelines. IJR moved for summary judgment on the issue of fair use, which the district court granted.

Left, Philpot’s photo; right, IJR’s use.

The Fourth Circuit reversed, finding that IJR’s usage of the photographs did not constitute fair use. As to the first fair use prong, the district court had found that IJR’s use was transformative, reasoning that since the photos accompanied articles they appeared in a new context. In rejecting this argument, the Circuit Court noted that as was the case in Warhol, IJR “did not alter or add new expression to [Philpot’s photos],” and accordingly its uses could not be found transformative. The court similarly found that the second, third, and fourth fair use factors did not support a finding of fair use.

Philpot vindicates the rights of content creators who share their work under alternative licensing models. The case can be read as a warning to online platforms and publishers that use of online content without ensuring compliance with licensing terms can lead to liability.

Griner et al. v. King et al.

And who could forget memes? Fair use got a meme-worthy twist this year in Griner v. King, 104 F.4th 1 (8th Cir. 2024), where the Eighth Circuit tackled the age-old question: is sharing memes copyright infringement?

In 2007, a woman named Laney Griner took a photo of her baby and posted it online. The image quickly went viral, and became an iconic internet meme, known colloquially as the “Success Kid” meme. In 2020, the election committee for Congressman Steve King posted a copy of the meme as part of a fundraiser for his reelection campaign. Griner sued. The case went all the way to a jury, which found in favor of Griner. King appealed.

King’s use of the “Success Kid” meme.

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed the jury verdict, finding that the use of the “Success Kid” meme template for campaign purposes was infringing and was not protected fair use. In reaching this decision, the court found that the use was not transformative under Warhol because King “did not add a further purpose or different character to [the] Success Kid template.” Id. at 9. The court also noted that as in Warhol, the commerciality of the usage weighed against King in this instance. Id.

The result raises more questions than it answers about the murky legal status of memes, which are generally designed to be shared and are ubiquitous on social media and our broader cultural milieu. Whether the case will have a further chilling effect on meme usage remains to be seen, but be sure to keep an eye out as you share the latest and greatest captioned Moo Deng photos in 2025.

Music Cases: Scaling back Williams v. Bridgeport?

This year we saw continued fallout from the 2018 Williams v. Bridgeport Music decision, which found Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke liable for copyright infringement of Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give it Up” to the tune of millions of dollars. The result was controversial, with critics arguing that the ruling could stifle creativity in the music industry going forward, as artists might fear legal action for drawing inspiration from existing works or genres.

Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran

Though plaintiffs continued to bring lawsuits in the style of Williams v. Bridgeport throughout 2024, one of this year’s key decisions, Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran, 120 F.4th 1066 (2d Cir. 2024) represents a step back from Williams v. Bridgeport and helps to illustrate what’s going on in the music industry. In its November 2024 ruling, the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling that Ed Sheeran’s 2014 song “Thinking Out Loud” did not infringe Marvin Gaye’s 1973 classic “Let’s Get It On.” Structured Asset Sales, which owns a portion of the royalties for Gaye’s track, had claimed that Sheeran’s song copied the chord progression and syncopated harmonic rhythm of Gaye’s composition.

In ruling for Sheeran, the court emphasized that under the Copyright Act of 1909, the scope of copyright protection for a musical composition is confined to the material present in the sheet music deposited with the Copyright Office at the time of registration. Consequently, elements from Gaye’s audio recording not included in the deposited sheet music were deemed outside the copyright’s protection. The court also determined that the combination of the four-chord progression and syncopated harmonic rhythm lacked the requisite originality for copyright protection, noting that such musical elements are commonplace in popular music.

Tempo Music Investments, LLC v. Miley Cyrus et al.

In September 2024, Tempo Music Investments came in like a wrecking ball and filed a lawsuit against Miley Cyrus, alleging that her hit song “Flowers” infringed upon the copyright of Bruno Mars’ 2013 track “When I Was Your Man.” Tempo Music, which acquired a portion of the rights to Mars’ song, alleged that “Flowers” duplicated several elements from Mars’ track, with a particular focus on lyrical similarities. No. 24 CV 7910 (C.D. Cal. filed Sept. 16, 2024). Cyrus filed a motion to dismiss in November 2024, which is still pending. It is worth noting that some fans have theorized that “Flowers” is a direct response to Mars’ song—Mars laments his lost love (“I should've bought you flowers/And held your hand”), whereas Miley retorts that she is better off without him (“I can buy myself flowers. . . And I can hold my own hand”). Insofar as that is true, Cyrus may have a credible fair use defense for the lyrical similarities of the songs, as fair use protects critique and criticism. The case will be one to watch in the new year and is indicative of the increase in litigation against hit songs we have been seeing since the Blurred Lines case.

The AI Explosion

Any summary of 2024 copyright litigation would be remiss not to mention the bevy of ongoing lawsuits implicating generative AI. The transformation of generative AI from a niche research subject to a commercial product in the past few years has brought up a host of novel copyright issues—and of course, plenty of litigation. While the legal status of generative AI is still very much up in the air when it comes to copyright—as none of these cases have yet been decided—there is plenty to learn from how these cases have played out so far.

Because there has been so much activity in the AI field, we have created a separate update on this topic alone, so please head on over to our 2024 AI Year In Review article on the Debevoise Data Blog.

Copyright in 2025?

The stage is set for 2025 to be another blockbuster year in copyright litigation. First up, the fight over generative AI is far from over. As artists, tech companies, and rights holders square off, expect heated debates over how far the doctrine of fair use can stretch in this brave new world of digital creativity.

Meanwhile, the entertainment industry is not sitting this one out. We expect music copyright disputes will continue to dominate headlines, with questions about originality, inspiration, and sampling being dissected like never before. Memes, tattoos, and other unexpected art forms are likely to continue popping up in pleadings, testing the boundaries of copyright law in everyday life. And with the Supreme Court hinting at its willingness to revisit damages and other major issues, 2025 could bring more landmark decisions that reshape the legal landscape for years to come.

This publication is for general information purposes only. It is not intended to provide, nor is it to be used as, a substitute for legal advice. In some jurisdictions it may be considered attorney advertising.