Key Takeaways:

- After Warhol, courts continued to wrestle with the first fair-use factor—the purpose and character of the junior use—demanding a clear reason for copying beyond just a “transformative” purpose. Cases like Romanova v. Amilus Inc., Lynk Media v. Independent Digital News and Media LLC and Monroe v. NorthStar Source Grp., LLC show that simply adding context is not enough; the secondary use must also engage with the original work itself and must not function as a market substitute.

- Secondary liability was another hot spot. Two major rulings upheld strong DMCA safe-harbor protections for platforms like Vimeo, and the Supreme Court is now reviewing ISP liability in Cox v. Sony. The Cox decision could redraw the lines for contributory liability and the balance between copyright enforcement and Internet access.

- A grab bag of cases showed how copyright doctrine continues to stretch into unexpected territory: the Supreme Court agreed to review a high-stakes separation-of-powers fight over the president’s authority to remove the Register of Copyrights; the Ninth Circuit tightened the pleading standard for “access” in the age of social media algorithms; and a New York district court rejected President Trump’s bid to claim joint authorship of his interviews with Bob Woodward, underscoring the central role of mutual intent and control in joint-authorship claims.

- Substantial similarity doctrine may be in flux. In Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a jury verdict for tattoo artist Kat Von D, but separate concurrences sharply questioned the circuit’s longstanding “intrinsic” test, signaling possible en banc reconsideration—and a potential rethinking of how courts assess infringement out west.

In this Debevoise In Depth, we break down last year’s key copyright developments and look ahead to what’s coming in 2026.

- After Warhol, courts continued to wrestle with the first fair use factor—the purpose and character of the junior use—demanding a clear reason for copying beyond just a “transformative” purpose. Cases like Romanova v. Amilus Inc., Lynk Media v. Independent Digital News, and Media LLC and Monroe v. NorthStar Source Group, LLC show that simply adding context is not enough; the secondary use must also engage with the original work itself and must not function as a market substitute.

- Secondary liability was another hot spot. Two major rulings upheld strong DMCA safe harbor protections for platforms like Vimeo, and the Supreme Court is now reviewing ISP liability in Cox v. Sony. The Cox decision could redraw the lines for contributory liability and the balance between copyright enforcement and Internet access.

- A grab bag of cases showed how copyright doctrine continues to stretch into unexpected territory: the Supreme Court agreed to review a high-stakes separation-of-powers fight over the president’s authority to remove the Register of Copyrights; the Ninth Circuit tightened the pleading standard for “access” in the age of social-media algorithms; and a New York district court rejected President Trump’s bid to claim joint authorship of his interviews with Bob Woodward, underscoring the central role of mutual intent and control in joint-authorship claims.

- Substantial similarity doctrine may be in flux. In Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a jury verdict for tattoo artist Kat Von D, but separate concurrences sharply questioned the circuit’s longstanding “intrinsic” test, signaling possible en banc reconsideration—and a potential rethinking of how courts assess infringement out west.

- AI litigation continued to explode in 2025, with a flood of new copyright suits filed against AI developers. The issue is so big, we gave it its own article. You can read our deep dive on AI and copyright here.

Copyright’s Big Year: 2025’s Defining Rulings and 2026’s Flashpoints

2025 was another landmark year for copyright law, marked by fast-moving tech, major legal shifts, and big-name disputes. From the aftershocks of Warhol to the continued explosion of AI litigation, courts wrestled with applying old rules to a new digital world. Courts made headway on interpreting fair use in the wake of Warhol, the music industry kept up its fight against online piracy, platforms scored big wins under the DMCA safe harbor, and the Supreme Court geared up to tackle ISP liability in Cox v. Sony.

No discussion of copyright in 2025 would be complete without addressing the unmistakable elephant in the room: generative AI. AI-related copyright litigation continued to explode over the past year, with a wave of new suits filed against AI developers and, for the first time, courts beginning to grapple with fair use defenses in this context. The issue loomed so large that it deserves its own treatment. We explore these developments and what they may mean for creators, platforms, and courts in a separate deep dive on AI and copyright, available here.

If 2025 was packed with legal twists and high-stakes fights, 2026 is shaping up to be just as important. As everyone from judges to tech companies grapples with copyright law, the developments of this past year set the stage for the battles—and breakthroughs—ahead.

Fair Use in the Wake of Warhol

Last year, we noted that the Supreme Court’s Warhol decision would keep courts busy through 2025, and we were right. The ruling’s focus on the first fair use factor—the purpose and character of the use—has started to blur the line between that factor and the fourth factor, which addresses market harm.

In 2025, New York’s federal courts were busy applying Warhol in cases involving online media. These rulings wrestled with a key question as part of their inquiry into the first fair use factor: what makes a new use truly “transformative”? While there is no clear-cut answer yet, these cases give us a glimpse of what a winning fair use defense looks like post-Warhol (or at least what it does not look like).

Romanova v. Amilus Inc.

In Romanova v. Amilus Inc., 138 F.4th 104 (2d Cir. 2025), the Second Circuit analyzed whether an online news site, owned by Amilus Inc., made a fair use of plaintiff Jana Romanova’s photo. Romanova, a professional photographer, had licensed the image at issue—a portrait of a woman with pet snakes—to National Geographic. Amilus reproduced the photograph in an article entitled, “Trending: Dogs, Cats ... and Other Pets, to Start Off 2018,” without permission.

Although the defendant had defaulted, Judge Caproni of the Southern District of New York sua sponte concluded that the use was fair. On appeal, the Second Circuit reversed, holding that there was nothing in the record to support a finding of fair use under Warhol and emphasizing that for the first factor to favor a defendant, the defendant must have a suitable justification for copying or incorporating the plaintiff’s work. Drawing on Warhol, the Second Circuit explained that transformativeness and the defendant’s justification for copying are closely linked. The court identified a non-exhaustive set of justifications that have supported fair use in other contexts, such as Google Books’ copying of books to create a database for identifying books. The court further identified a consistent theme across examples where fair use applied: the junior use does not serve as a market substitute for the original. Id. at 115–17.

Applying this framework, the court concluded that Amilus’s use was neither transformative nor justified—simply reproducing another’s work and “asserting some fact about” it does not qualify as fair use. Id. at 119. The court explained that a transformative and justified use in this context would likely require commentary on or criticism of the photograph or its author. Id. at 120.

While Romanova offers meaningful guidance on how courts may approach the first factor inquiry post-Warhol, it also raises questions about the tension between transformativeness and justification as the primary driver of the inquiry.

Lynk Media v. Independent Digital News and Media, LLC

Four months after Romanova, the Southern District of New York once again grappled with the first fair use factor in Lynk Media, LLC v. Independent Digital News & Media, LLC, No. 24 CV 583, 2025 WL 2771625 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 29, 2025). The case involved a videographer, in the business of creating and selling videos to news organizations, who sued after The Independent embedded social media posts containing her videos into its articles without permission. The videos at issue depicted, among other things, a political rally in Pennsylvania, an anti-vaccine mandate protest in New York and a puppy guard dog on the frontlines of the war in Ukraine. The defendant argued that embedding the posts was transformative because the articles commented on the controversial topics depicted in the videos.

The court rejected the fair use argument and granted summary judgment for the plaintiff. Drawing on Romanova, the court subdivided the first fair use factor into three components—transformative purpose, commerciality, and justification—and concluded that none favored the defendant. Id. at *15–18.

The court explained that the use was not transformative because both the original and secondary uses served the same function: documenting current events. Id. at *15. The court held that it did not matter that the secondary use commented on the surrounding online discourse because it did not transform the underlying work itself. The defendant also failed to establish sufficient justification for copying. The articles did not critique or comment on the videos as creative works but, instead, used them to illustrate the events they depicted. The court further noted that permitting news outlets to freely reuse publicly posted images and videos simply because the subject matter is newsworthy would undermine the licensing markets on which creators like the plaintiff depend—which once again implicates the fourth factor’s focus on the market effect of the secondary use. Id. at *17.

Lynk illustrates how courts may continue applying Romanova’s post-Warhol framework by placing the defendant’s justification for the use at the center of the first factor analysis, and the decision underscores that defendants should be prepared to articulate a concrete rationale for copying.

Monroe v. NorthStar Source Group, LLC

Not all judges in the Southern District of New York have explicitly adopted Romanova’s justification framework, but their fair use analyses often have yielded similar outcomes. In Monroe v. NorthStar Source Group, LLC, No. 1:23-cv-06220, 2025 WL 1939027 (S.D.N.Y. July 15, 2025), Judge Ho addressed whether an Instagram account infringed a photographer’s copyrights by reposting his images without permission. Without expressly considering the defendant’s justification, the court followed reasoning that echoed the approach in Romanova and Lynk and ultimately granted summary judgment for the plaintiff.

The defendant took 11 photographs of prominent 90s hip-hop and R&B artists from photographer T. Eric Monroe’s website, cropped out his watermark and posted them on an Instagram account dedicated to preserving and celebrating hip-hop culture. The defendant claimed the posts “recontextualized” the images by highlighting their historical significance through hashtags such as #sourceclassics and #throwback, id. at *6, as illustrated by the example below.

Monroe’s photograph reposted by @thesource

The court disagreed. In analyzing fair use, the court largely decided the first factor on the question of transformativeness. Though not explicitly referencing Romanova, the court made a similar observation that there is no transformative use when a secondary user merely reposts the original work with additional context but is not commenting or criticizing the original work. Id. at *6. The court stated that “[defendant’s use] amounts to exploitation of Monroe’s original creative work for the same purpose, which is to display images of iconic hip-hop artists,” id. This point was reminiscent of the argument in Romanova and Lynk that the non-transformative purpose does not justify the copying because such a use merely exploits the original work.

On the fourth factor, the effect of the use on the market, the court highlighted the fact that Monroe frequently licensed his photographs to other media sources and that unlicensed uses therefore harm the works’ market value. Id. at 8. As in Lynk, the court was sensitive to the reality of online news media licensing; authors often post their works on their own websites or profiles to generate licensing demand, and online media companies are still expected to license that work for their own use, despite the works’ online availability.

Up Next in Fair Use

Going forward, we expect to see courts continue to struggle with what it means to make a transformative, justified fair use in contexts that have emerged alongside new forms of online entertainment.

A series of cases to watch are those filed by Ethan and Hila Klein in response to what the Kleins’ call “lazy reaction videos.” In Ted Entertainment v. Denims, which the Kleins filed in June 2025, the complaint alleges that a Twitch streamer known as Denims infringed the Kleins’ copyrights by playing their videos—Content Nuke: Hasan Piker and The Countdown to Doomsday—in full during a livestream at the moment of release, without providing meaningful commentary or criticism. Ted Ent. v. Denims, No. 2:25-cv-05564 (C.D. Cal. 2025). Two other cases filed by the Kleins, Ted Entertainment v. Majed and Ted Entertainment v. Caviness, contain similar allegations. Ted Ent. Inc. v. Morgan Kamal Majed, No. 2:25-cv-05565 (C.D. Cal. 2025); Ted Ent., Inc. v. Caviness, No. 4:25-cv-00459 (W.D. Mo. 2025).

Denims on Twitch.

These cases raise novel questions about the boundary between legitimate commentary and so-called “reaction” content. How much commentary is required to justify extensive copying? Does the depth or substance of the commentary matter? And to what extent should courts assess the proportionality between the original work and the secondary user’s additions? As courts apply Warhol and Romanova’s focus on justification to new digital formats, these cases may offer an early test of how those principles translate to livestreamed reaction media.

Facing the Music: Vimeo, Cox, and Online Liability

The music industry continues to be ground zero for major online liability cases that affect the entire Internet. This year saw two big decisions from the Second Circuit affirming Vimeo’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) safe harbor protections. And, looking ahead, the Supreme Court is set to rule on ISP liability in the closely watched Cox v. Sony.

Capitol Records v. Vimeo

The Second Circuit’s decisions in Capitol Records v. Vimeo marked one of the most consequential developments in secondary liability and DMCA safe-harbor doctrine in 2025.

In 2009, record companies Capitol Records and EMI sued the video platform Vimeo for copyright infringement, alleging that hundreds of user-created videos on Vimeo contained infringing uses of copyrighted musical performances.

In January, after more than a decade of litigation, the Second Circuit affirmed that Vimeo was protected from liability by the DMCA safe harbor in Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, Inc., 125 F.4th 409 (2d Cir. 2025). The court explained that to show Vimeo had forfeited the safe harbor through “red flag” knowledge of infringement, the plaintiffs were required to demonstrate that it would have been “objectively obvious” to Vimeo employees—who lacked copyright training—that the uses of the music at issue were neither licensed nor excused by fair use. Id. at 420–21. The record labels were able to show only that Vimeo employees had viewed certain videos, which the court held was insufficient.

The Second Circuit also rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that Vimeo had the “right and ability to control” infringing activity for the purposes of disqualifying the safe harbor. The court found that Vimeo exerted minimal influence over user content and did not meaningfully direct or curate videos, even when it promoted particular works. Id. at 425. The platform’s bans on pornography and gameplay content likewise did not amount to control, as these policies reflected lawful business judgments of the sort that the DMCA safe harbor was meant to encourage. Id.

After a rehearing, the Second Circuit reaffirmed its ruling in a September decision, though it removed a footnote in the January opinion that would have foreclosed Supreme Court review. Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, Inc., 151 F.4th 13 (2d Cir. 2025).

Whether the case will proceed to the Supreme Court remains uncertain. For now, Vimeo stands as a significant victory for online service providers, reinforcing that the DMCA safe harbor remains intact and that its exceptions continue to be interpreted narrowly.

Cox Communications v. Sony

In one of the most anticipated decisions of 2026, we will see the Supreme Court’s take on the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Cox v. Sony. Alongside the Second Circuit’s Vimeo decision, the Supreme Court’s upcoming review in Cox underscores the rapidly evolving boundaries of secondary liability for online intermediaries—where the DMCA safe harbor does not apply. Industry members and legal experts have filed countless amicus briefs on both sides, and on November 10, 2025, the Court granted the government’s request to participate in oral arguments in support of Cox.

The dispute concerns the unlawful downloading and distribution of music by subscribers of Cox, an Internet and cable provider. Sony and other record companies, which own rights to more than 10,000 works at issue, prevailed at trial after Cox was found ineligible for the DMCA safe harbor based on an earlier decision. A jury found Cox willfully liable for contributory and vicarious infringement and awarded $1 billion in damages. On appeal, the Fourth Circuit reversed the vicarious liability finding for lack of a direct financial benefit but upheld the contributory liability verdict and remanded on damages. The court concluded that Cox had been presented with evidence of repeated, specific infringement notices yet continued providing service to repeat offenders, supported by what it described as “increasingly liberal policies and procedures for responding to reported infringement on its network.” Sony Music Ent. v. Cox Commc’ns, Inc., 93 F.4th 222, 236 (4th Cir. 2024), cert. granted, 145 S. Ct. 2841 (2025).

Cox argues that affirming the contributory-liability ruling would “def[y] common law and common sense,” contending that an ISP does not “purposefully participate in” subscribers’ infringement any more than a phone company or delivery service participates in the content it transmits. Cox and its supporters warn that the Fourth Circuit’s approach could lead ISPs to terminate vast numbers of users, potentially restricting speech and access to information. Rights holders, by contrast, emphasize the practical impossibility of pursuing individual infringers in the digital age and argue that meaningful copyright enforcement requires holding intermediaries accountable when they knowingly facilitate repeated infringement.

The case was argued before the Supreme Court on December 1, 2025. As we reported at the time, the Justices seemed concerned about both parties’ positions during oral argument—on the one hand, Cox’s proposed heightened standard for contributory liability that would effectively leave ISPs with no legal incentive to act against repeat infringers and, on the other hand, rights holders’ position that ISPs must terminate access where they have knowledge of infringement, even in the contexts of multi-user Internet licenses that could impact thousands of innocent users. Whatever the outcome, the Supreme Court’s decision is poised to have far-reaching consequences for the balance between copyright enforcement and Internet access—and may reshape secondary-liability doctrine for years to come.

Copyright’s Stranger Things: Other Cases You Might Have Missed

So, what else happened in 2025? More than we can cover in one article. But here is a quick look at a few other noteworthy cases that are distinctive, unusual or just plain instructive.

Perlmutter v. Blanche

In May, the Copyright Office became embroiled in drama after President Trump dismissed Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter just one day after the Copyright Office released a pre-publication report on AI recommending limits on the use of copyrighted material for AI training. Perlmutter challenged her removal, and in September, a divided D.C. Circuit panel ordered her reinstatement. Perlmutter v. Blanche, No. 25-5285, 2025 WL 2627965 (D.C. Cir. Sep. 10, 2025). The Supreme Court has agreed to review the decision, which will require the Court to consider whether the Register—housed within the Library of Congress—may be removed by the president on the theory that the position exercises executive authority. The Court’s resolution of that question may depend in significant part on its forthcoming decisions in Kelly v. United States and Cook v. United States, which address the scope of presidential removal authority over officials outside the Executive Branch. The Court already has heard argument in Kelly. Based on the tenor of the majority’s questioning—which evinced skepticism toward limits on removal authority—the outlook may be unfavorable for Perlmutter.

Woodland v. Hill

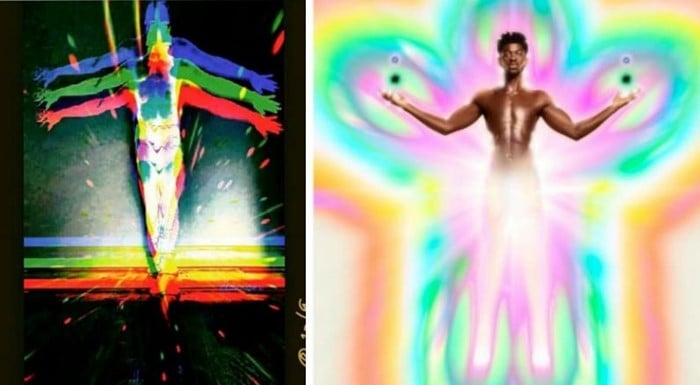

In Woodland v. Hill, 136 F.4th 1199 (9th Cir. 2025), the Ninth Circuit affirmed dismissal of a lawsuit alleging that Lil Nas X copied several semi-nude Instagram photographs that freelance artist Rodney Woodland posted. Woodland attempted to plead access by alleging that, because Lil Nas X and Woodland post similar content, the Instagram algorithm would likely have recommended Woodland’s posts to Lil Nas X. The Ninth Circuit rejected that theory, emphasizing that while the Internet and social media have made it easier to allege that a work was widely available, availability is not the same as access. In the context of social media platforms, the court explained, a plaintiff must plausibly allege that “the defendants had a reasonable chance of seeing [the plaintiffs’] work under that platform’s algorithm or content-sharing policy.” Id. at 1209. Woodland failed to do so here: although Woodland and Lil Nas X posted similar content, there were no factual allegations supporting the inference that Instagram’s algorithm would push one user’s content to another merely because of that similarity. At the same time, the decision suggests a potential roadmap for future plaintiffs, as the court indicated that evidence that a defendant follows, likes, or otherwise interacts with posts or accounts could be relevant to the access analysis. Woodland since has asked the Supreme Court for an extension of time to file a petition for certiorari. The Woodland decision reflects an effort to adapt traditional access principles to the realities of modern online distribution.

Left, Woodland’s photograph; right, Lil Nas X image

Trump v. Simon & Schuster

Finally, in July, the Southern District of New York dismissed President Trump’s claim that he was a joint author of 20 interviews conducted by Bob Woodward and later released in audiobook form as The Trump Tapes: Bob Woodward's Twenty Interviews with President Trump. Trump v. Simon & Schuster, Inc., 791 F. Supp. 3d 470 (S.D.N.Y. July 18, 2025). To highlight an interesting wrinkle, President Trump’s counsel filed an application to register the copyright in The Trump Tapes as a work of sole authorship while the case was pending, with Trump listed as the sole author. In dismissing the suit, Judge Gardephe held that President Trump failed to plausibly allege that he had intended to create a joint work with Woodward at the time of the interviews; in fact, the complaint showed that he had “never agreed, understood, or intended that the interviews would be used for any purpose other than Woodward’s upcoming book Rage.” Id. at 487. The court also considered Woodward’s role in formulating the questions for the interview and editing the recordings together, emphasizing the importance of mutual authority and control, along with mutual intent, when it comes to evaluating joint authorship.

The End of the Year … And the Intrinsic Test?

While everyone was resting over the holidays, the Ninth Circuit was not. On January 2, 2026, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a jury verdict in favor of tattoo artist Kat Von D in a long-running dispute over whether her tattoo of jazz legend Miles Davis and related social-media posts infringed photographer Jeffrey Sedlik’s copyrighted image. Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, No. 24 CV 3367, 2026 WL 17166 (9th Cir. Jan. 2, 2026). The jury had concluded that the tattoo, the preparatory sketch, and most of the posts were not substantially similar to Sedlik’s photograph under the Ninth Circuit’s longstanding “intrinsic” or “total concept and feel” test and that certain process posts were fair use. The appellate panel declined to disturb those findings. However, the decision drew unusually pointed concurring opinions from two judges who agreed only in the result, openly criticizing the intrinsic test as fundamentally flawed and urging that the court reconsider or scrap the doctrine that has governed Ninth Circuit substantial similarity analysis for decades. Those concurrences could lay the groundwork for en banc review and a potential overhaul of how the court evaluates infringement in cases involving artistic works and modern media.

Also in early January, two copyright decisions involving Top Gun: Maverick reinforced the boundaries of what copyright law protects and what it leaves open to others. In Yonay v. Paramount Pictures Corporation, the Ninth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Paramount, holding that the 2022 sequel did not infringe the copyright in Ehud Yonay’s 1983 magazine article that inspired the original Top Gun film because the similarities lay in unprotectable facts about the Navy’s fighter-pilot program rather than in protected expression. Yonay v. Paramount Pictures Corp., No. 24 CV 2897, 2026 WL 17168 (9th Cir. Jan. 2, 2026). Days later, in Gray v. Paramount Global, the Southern District of New York dismissed a suit filed by a writer who claimed he had contributed scenes to Top Gun: Maverick without a contract, ruling that his work was an unauthorized derivative built entirely on Paramount’s existing material and therefore not entitled to copyright protection. Gray v. Paramount Glob., No. 25 CV 3484, 2026 WL 71421 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 9, 2026). Taken together, the rulings illustrate the “hard deck” of copyright’s danger zone: crossing into another’s protected expression without permission yields no rights, and claiming ownership over mere facts or ideas garners no protection at all.

What’s Next for Copyright in 2026?

Taken together, the developments of 2025 reflect a copyright landscape in rapid transition. Courts refined the contours of fair use in the wake of Warhol, revisited the scope of secondary liability for online intermediaries and confronted foundational questions about the legality of AI training. At the same time, cases involving government agencies, social-media conduct, and claims of joint authorship demonstrated how traditional doctrines continue to evolve in response to modern technologies and cultural shifts. Whether through the emergence of new litigation frontiers or the reinvigoration of longstanding principles, 2025 underscored the extent to which copyright remains a dynamic area of law.

Looking ahead, appellate courts will take center stage in shaping the future of AI and copyright. One of the most anticipated decisions will come from the Third Circuit in Thomson Reuters v. ROSS, which presents the first appellate review of a district court’s holding that AI training may fall outside fair use. The court’s treatment of originality, transformativeness and market substitution could meaningfully influence how similar claims are litigated nationwide. At the same time, the Ninth Circuit may also confront key questions involving torrenting and acquisition of copyrighted materials as the Kadrey v. Meta litigation progresses, particularly if Meta challenges future rulings on the storage or reproduction of pirated works.

Beyond AI, 2026 may bring consequential shifts in secondary liability doctrine. We eagerly await the Supreme Court’s decision in Cox v. Sony, a case that could redefine the obligations of ISPs when responding to infringement notices.

Finally, courts will continue to grapple with doctrinal questions that extend beyond any single case. In the fair use arena, cases like Ted Entertainment v. Denims will test how Warhol applies to contemporary online formats such as livestreamed reaction content. In the entertainment and publishing sectors, follow-on litigation may arise from the massive settlement in Bartz v. Anthropic, particularly as authors weigh whether to opt out and pursue individual claims. Together, these developments ensure that 2026 will be another formative year—one in which courts, policymakers, and industry participants continue to negotiate the balance between innovation and creators’ rights.

This publication is for general information purposes only. It is not intended to provide, nor is it to be used as, a substitute for legal advice. In some jurisdictions it may be considered attorney advertising.